Writing a history of the internet is a lot like browsing the network itself. There’s a lot of information about, much of it contradictory. Some of that information is laced with conspiracy theories, some of it is unverified. Claims are made by anonymous sources, some of whom have personal vendettas. And by the time you’re done with it all, you feel slightly dizzy, not quite sure of what’s real and what isn’t.

There is one history of the internet that is simple; the kind you’ll find in a textbook or a Wikipedia entry catered for audiences living in the Anglosphere. In this history, the internet begins as a series of experiments in the 1960s and 70s, undertaken by scientists working in the US Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency Network – known as ARPANET. The project was initially designed to allow four computers to exchange data – a fairly mundane task at the time, with the immense possibilities of the project as yet unforeseen.

From this humble origin story, the history of the internet becomes a narrative of continual progress. This simple networking experiment, the story goes, turned into a larger group of computer networks in the 1980s, spreading through to university campuses across America. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee created hypertext transfer protocol, aka “http”, which allowed different computers to interact with each other across the World Wide Web.

If you had a niche hobby, weird interest, or a tingling curiosity, there was a specific website with hundreds of people like you

The 1990s saw the creation of the first web browsers and, eventually, the first websites. These browsers were founded on a similar ethos – that information should be free to distribute and share, and that true freedom came not from governments or free market economics, but through the connections people made with each other. Nowhere was this ethos better described than in 1996, when John Perry Barlow founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation – the first civil rights group for the internet age. In his Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, Barlow wrote:

“I declare the global social space we are building to be naturally independent of the tyrannies you seek to impose on us […] We are creating a world that all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth.”

This might seem like an unfamiliar vision of the internet. In 2019, so much of our life online is defined by what happens on just a few platforms. Whether that’s election rigging via Twitter bots, industrial amounts of “fake news” being spread around Facebook, extremist movements organising over Whatsapp, or the world’s advertising industry shifting its resources to Instagram, the internet is not short of “tyrannies”. How did we get here?

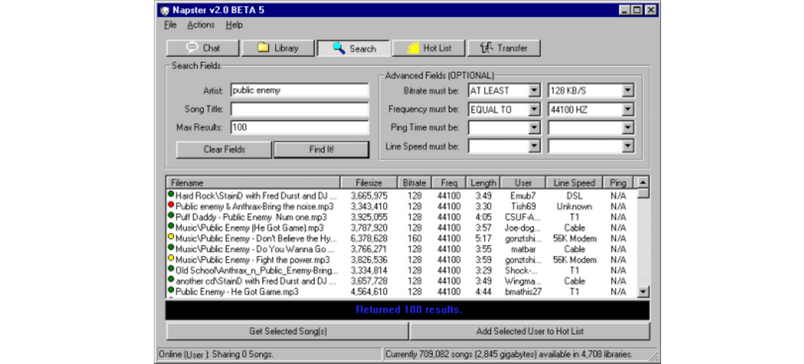

In the late 90s and early 2000s, the internet was structured on the basis of decentralisation. There’s no better example, in the West, than music sharing. In 1999, there were many speculative claims about a piece of software called Napster – the first “peer to peer” music sharing service, where anyone could download any piece of music they wanted. While we’re now used to having easy access to music via Spotify or iTunes, the tech was revolutionary at the time. While music streaming services today are centralised – ie. you download “Dancing Queen” by ABBA directly from Spotify – in 1999, you would download pieces of “Dancing Queen” from multiple computers formed in a network that spanned across the world. Instead of downloading the song from one place, you could download it from over a hundred places, all at once.

In 2001, Napster was forced to shut down after being defeated in court by the Record Industry Association of America, who argued that the service breached multiple copyright laws, and was decimating the music industry. But while Napster may be a thing of the past, its peer-to-peer technology defined the next five years of the internet (ironically, its founder, Sean Parker, went on to further define our current social media age when he became president of Facebook in 2004). The peer-to-peer system of sharing gave rise to other fixtures that defined internet culture for that period.

A ‘decentralised’ internet has slowly transformed into one that is increasingly centralised, dominated by a handful of big technology companies

Software like KaZaa, Bittorrent, Limewire and Emule were all constructed off the back of peer-to-peer file sharing, providing a near endless supply of music, movies, television, and comic books that could be accessed with a few clicks of a mouse. Of course, there were risks with downloading in this way. Sometimes, people who uploaded material onto the peer-to-peer networks laced the content with malicious code, which, when the file was opened, would result in your computer crashing, being infected by a virus. Worse, if you only had one computer – the “family computer” in your house – you never knew if you had actually downloaded the latest Ja Rule or The Strokes album, or if you’d once again accidentally downloaded virus-laden porn.

At the time, getting anti-virus software like McAfee or Norton Antivirus was expensive. Moreover, it couldn’t be downloaded directly from the internet, so every time you tried to download an episode of Prison Break or Lost, there was a risk that you’d end up having to buy a new hard-drive the following week. Still, peer-to-peer networks changed the way that people enjoyed entertainment. It created a culture we’re familiar with today – one where immediacy was of the utmost importance, and, more importantly, where cost no longer prohibited access to pop culture. Anyone with access to a computer could get access to entertainment, and could be part of online communities – situated on message boards and forums – that would allow people to come together on the basis of their shared interests.

Because of government regulation and extensive lawsuits, peer-to-peer file sharing is less common than it used to be, but its cultural impact is immense. It helped create a culture where media companies needed to make content on demand while also ensuring that users were safe. It showed how a network of thousands of computers could be created from a bedroom, something completely unprecedented in modern home computing. That technology, which was once considered to be a niche interest for nerds, not only led to the creation of video-streaming platforms like Netflix, it was also instrumental in forming new ideas about how society could and should work. The best example of this is cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, the existence of which was built from trading across peer-to-peer networks.

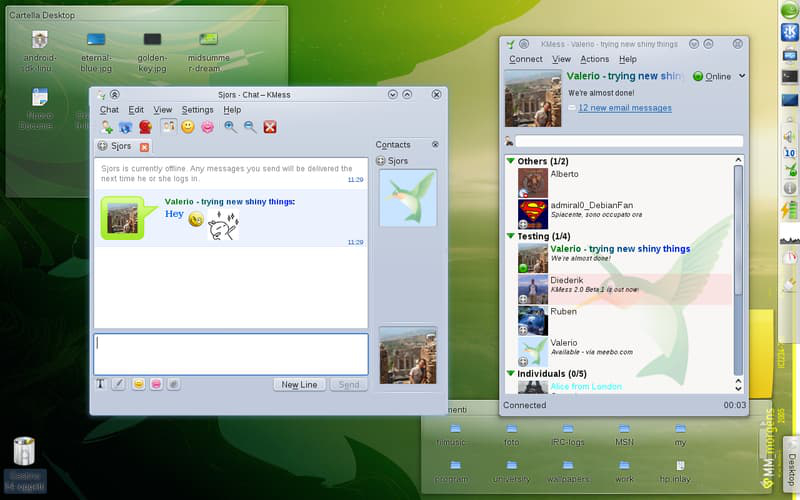

The development of internet culture in the mid 2000s also laid the groundwork for an innovation we now consider to be standard online: social media. While the first online message boards were active in the 1970s – as bulletin boards designed for companies to advertise their products and services – it was social networks like Classmates.com and Friends Reunited, both staples of the late 1990s and early 2000s, that presented the internet as a tool to connect with people socially. Later, MSN Messenger – an instant messaging program developed by Microsoft in 1999 – became one of the first networks to allow users to connect with friends and strangers in real time.

MSN touched the lives of millions of teenagers – including myself – before the advent of modern social networking. It was one of the first social networks to bring obscure online acronyms, which were once restricted to niche communities, to the mainstream. Phrases like “A/S/L?” – meaning “age, sex, location” – allowed me to connect with people all over the world. “U There?” became a go-to phrase when you weren’t able to sleep and were looking for anyone to talk to in the quiet hours of the night. Basic emojis, like “:)” and “:s” could hold thousands of different meanings depending on who you were talking to, whether they were just friends, or if you were trying to ask them out on a date. MSN might have been a basic build by the standards of modern messaging services, but it had a profound impact on how we communicated with other people online.

It wasn’t just instant messaging services that influenced the internet as we know it today. In the mid-2000s, more advanced forums began to foster the niche online communities that made the internet such a special place. Forums like The Temple of the Screaming Electron (Totse) and Zoklet provided gateways to what was known as the “deep net” – a place where, under pseudonyms, users could talk openly about the most taboo of subjects, ranging from where to get psychedelic drugs to guides on how to hack a vending machine. Forums like 4chan – which are now considered to be hubs for the internet’s far-right communities – had once been a spot for tech nerds and video game enthusiasts, a place where you could indulge in all things geek culture, at a time when there was little evidence to suggest that comic books could be made into successful film franchises.

If you had a niche hobby, a weird interest, or even just a tingling curiosity, it was likely that there was a specific website or forum where hundreds, if not thousands, of people shared the same interest. There was always a place where you felt like you could belong and where you knew that you weren’t alone.

Today, more than four billion people are connected to the internet. While in 1995, only one per cent of the world’s population had access to the web, that number has risen to over 40 per cent, with more and more people connected every day. Yet while the number of users is increasing, there have been substantial changes to how we see and use the internet today.

The next generation of internet users may not have the space to be curious, or find themselves in an international community of people like them

If you go online today, it’s unlikely you’ll be clicking through to your favourite niche website, or messageboard – rather, you’ll go on your Twitter feed, a Facebook group, or a WhatsApp chat. You’ll download music directly from Spotify, and upload your photos to Instagram, complete with a stock filter. If you’re younger, you might make a quick video on TikTok – 2019’s answer to Vine, a social network that allowed users to upload six second videos of themselves before being acquired and later shut down by Twitter. You might watch your favourite movies on Netflix, or your favourite sports clips on YouTube – the latter of which is of course owned by Google, a company which dominates not just search, but maps, browsing, and even eye-tracking tech.

Reflecting on the past paints a picture of a “decentralised” internet that has slowly transformed into one that is increasingly centralised, dominated by a handful of big technology companies. This centralisation has opened up broader discussions and debates about how we use the internet.

The early days of the internet saw panics relating to Y2K (or “the millenium bug”), moral panics about dangerous, illegal, and pornographic content online, and ethical debates about the illegal downloading of movies. But today – at a time when most people in the western world have accepted the internet as a modern way of life, and some politicians have even claimed high speed internet is a human right – our discussions are more often than not about the risks the internet poses to our individual privacy.

In 2013, The Guardian famously uncovered evidence that the National Security Agency (NSA) had covertly installed software online that collected the data of millions of internet users. The 2016 pro-Brexit campaigners Vote Leave became mired in scandal regarding its employment of Cambridge Analytica, a company that allegedly hived the data of 50 million Facebook users and used it to target them with political advertisements. In the aftermath of the US election, questions are still being asked about Russian interference in American democracy via thousands of online bots.

How much data are we really handing over to big tech companies? How much of that data is being given to governments and security contractors? How much do big tech companies know about us? And does this mean that we are no longer free?

I still love the internet. I love connecting with others, hearing their stories and experiences, and seeing how they choose to express themselves. Connection is easier than ever, and it’s easy to see how the internet can be considered “addictive”. It is likely that the future of the internet will be even more dependent on algorithms and data collection. It’s also likely that as concerns about the internet’s reach continue to haunt governments around the world, they will advocate for more regulation and state control over the flow of information. In the UK, campaigners are currently warning about the government’s proposed “porn ban”, which, if passed into law, will require users to purchase a “porn pass” from local shops in order to access 18+ content. Activists say that this restriction will not only limit our online freedoms and pose a dangerous threat to privacy, it will also decimate independent creators of adult content, especially women directors, and transgender adult performers.

Undoubtedly, the internet will be radically different for future generations of web users. There are risks that the internet is transforming from a place with endless opportunities – for learning, creating and networking – into a place where only the wealthy and most established platforms will have the resources required to survive. The next generation of internet users may no longer have the space to be curious, or to find themselves in an international community of people like them. They may never experience the magical, unexpected online moments that redefine the way they see themselves or their place in the world. If a situation like that becomes reality, we may lose everything that made the internet great.