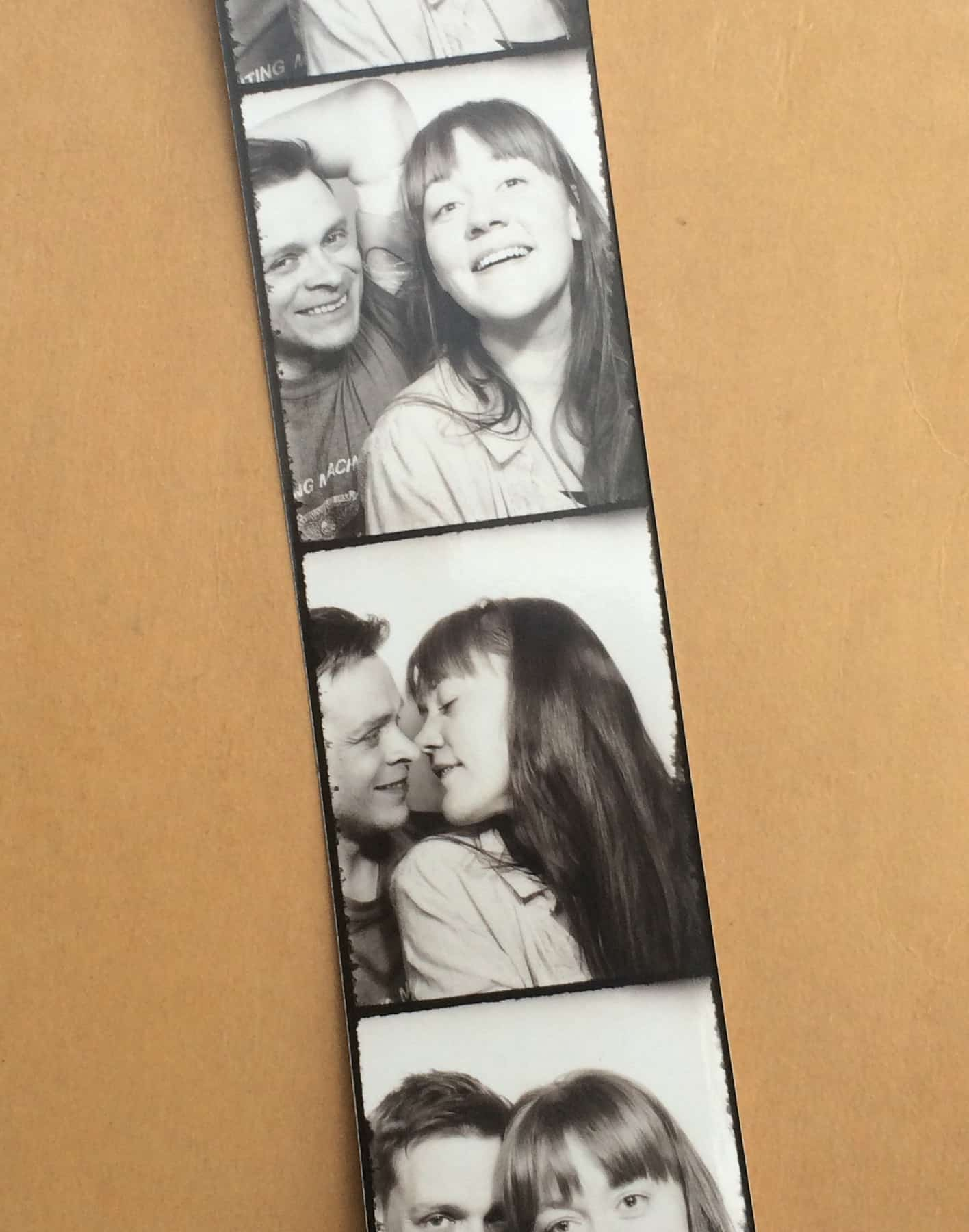

One of my favourite keepsakes is a strip of pictures from a Berlin Photoautomat – a streetside photobooth that spits out a strip of four black and white shots in exchange for €2. It was July 2016 and I’d gone on holiday for the first time with my partner, five months into a relationship we were both starting to realise was something unique, and while we have plenty of digital pictures from that trip, our photobooth shots are the most memorable.

A year later, we went back and repeated the experience, but this time the photos didn’t look as great – my eyes were closed in one of them, and in another I was scrunching up my face. But this is film photography: you get what you get. I wanted to toss the strip but my partner convinced me that we should keep it. This is how the photos turned out, he said, and who knows, these might be the only bad photos of ourselves that we’ll ever keep.

Photography used to be like that: you put film into a camera and hoped for the best as you took 12, 24, or 36 shots. Picking up the developed negatives after a week of waiting was exciting – you would eagerly leaf through the photos, slotting your favourites into an album, and even keeping the blurry, red-eyed shots (it was better than having no photos at all). In time, you’d often come to see those misfires as a beloved part of your personal memory archive.

For most of us, photos aren’t just pictures, but an important way to remember our lives. In the past, people might save photo albums from fires or floods – this is no longer necessary, as most of our pictures are safely backed up on some remote server in the cloud, available from any place at any time. But the transition from analogue to digital photo storage has been a rough ride, and we’re not out of the woods yet: most of us who took photos over the past decade or two will have lost some of them, or even all of them.

We abandoned our old habits without a proper plan for the future

In the excitement of new technology, the way that we preserve our personal memories has been interrupted – we abandoned our old habits without a proper plan for the future.

Many people stopped printing their pictures once everything went digital – a 2015 survey by Fujifilm found that only 43 per cent of people bothered to print their photos at all. But even though cameras became commonplace in the early noughties, early digital storage was in no way permanent. People had to delete photos as memory card storage was extremely limited, and hard drive copies were lost when a computer crashed, while mobile photos disappeared with a lost phone.

I have physical photo albums of all my photos until I got my first digital camera in about 2003, and I have a digital photo album from 2008 when I joined my first social media platforms. But my remote photo storage situation is precarious, and there’s a five year gap where I don’t have much of anything. Why did I let this happen? I’ll tell you why: I didn’t think.

My friend Matt Thomas is the only reason why I have an online photo archive at all – he’s the one who got me into Flickr, the online photo storage service, when we met 11 years ago. Sharing photos with others was part of the draw, but unlike many other social networks, Flickr has an archival quality which may explain why I’ve stuck with it all these years. Even when other social platforms became more popular, I appreciated how Flickr kept my photos safe in one place as I changed cameras, laptops and phones. But as the years passed, my attachment to Flickr became more of a default: this was now the only copy of almost all the photos I’d taken for a decade. Would I wake up one morning and find my memories gone?

“I’m in the same boat as you,” Matt tells me as we’re drinking coffee on a bench in East London – Flickr has the only copy of his photos too. “I’m properly locked into Flickr now, as long as they run it. It’s ransom,” he laughs. Matt’s referring to Flickr’s $50 (£38) annual storage fee, which has just been reinstated for accounts with more than 1,000 photos. We’ve both paid it with a shrug – we both spent a lot of time curating those digital albums and it feels like they have us over a barrel.

Matt’s Flickr archive goes back to when the service was founded in 2004. “I got a little digital camera that year and I didn’t take any more film photographs after that, nor was I backing up in any way outside of Flickr,” he says. Storage was expensive back then: hard drive prices have dropped steadily over the years, from around £7 per gigabyte in 2000 to less than 2p per gigabyte today. “I didn’t have any kind of plan for long-term storage.”

Matt has a two-year-old daughter now, and he’s thinking about storing memories in a different way. “I’d love to print all my photos on Flickr and turn them into books. I don’t want another digital copy so this [uncertainty] could happen all over again. I want my my archive realised into a physical thing. I’d pay a lot of money for that.”

Matt’s nervousness over his Flickr archives isn’t just paranoia. The once-cult-status company has changed hands several times, with each new owner coming in with new ideas as to what it should be. Flickr was bought by Yahoo! in 2005, subjecting users to numerous changes – Is it a storage site? Is it a social network? – as the parent company declined in tandem with Google’s rise. My stress peaked in 2017 when Yahoo! was bought by Verizon, and was only moderately alleviated in April of last year when photo hosting service SmugMug bought Flickr from Verizon with a promise to maintain it as a place that takes photography seriously.

Don MacAskill, CEO and Chief Geek of SmugMug and Flickr, was a good sport about my nervous questions when I called him in Mountain View: is Flickr going help me out of the mess I’ve made with my shoddy photo storage habits? “We’d certainly like to try,” he laughs. “The safety of people’s photos – their priceless memories and works of art – is the most critical and important thing for us.”

But the headlines haven’t been forgiving about the fact that from March 2019, Flickr will start deleting the photos of non-paying users (free users will only be allowed to keep 1,000 pictures). In November, Flickr gave its users four months’ notice – pay the fee, or find alternative arrangements for your collections. John, a 27-year old Flickr user from Edinburgh, told me via Twitter DM that March’s deletion spree will take his archive with it, because he’s lost access to the email address that he used to sign into Flickr.

“I’ve accepted it,” he says, resigned. “I used to work as a photographer and put my portfolio pictures on Flickr. It’s still some of my favourite work, but I think it will be lost for good.” John is going to download some of the publicly-available photos he has uploaded, and lose the rest.

The hard truth about the internet is that nothing is ever fully free. We’ve seen enough headlines about dodgy data mining to know that these companies aren’t necessarily our friends – if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. For paying customers, Flickr has done a decent job of keeping photos safe – unlike many social media sites, it retains the photos in their original size and keeps the metadata that’s captured by the camera.

“They’re your photos – they’re not our photos. Not every platform feels that way,” MacAskill says. This is important if it’s your only copy: if you’ve downloaded photos from Facebook you’ll know that many platforms don’t store photos in high resolution and what you get back is tiny.

Yet the change at Flickr is a stark reminder that internet companies change their minds all the time about what they want to do with our data – and in this case, our memories. For some, Flickr’s annual fee of £38 is out of reach, and for others it’s galling to face a bill for a service that used to be free. This turn of events can feel unfair – like memories are only for people who can afford them – but despite how we may feel about the internet companies we grew up with, they aren’t charities or public services.

Our digital habits could be endangering our entire visual history

“People seem to be getting more aware that free services are either unsustainable, or they are not free,” says MacAskill. “People are certainly waking up to the fact that if they care about their photos, or other [data], they should be more intentional about where they choose to put them.”

In 2015, the Professional Photographers of America called people like me the “lost generation”, arguing that our digital habits could be endangering our entire visual history. The moment of awakening that MacAskill is talking about – when you realise that a decade of your memories are held by an American internet company which may be pivoting into the abyss – doesn’t come when you’re 22. Usually it’s some big life event (death, marriage, a new baby, a house fire) that triggers nostalgia. Looking back helps us understand who we are. I’m the perfect candidate to have a moment like this: a so-called “older millennial” who’s closer to 40 than 30, who stopped printing before auto-backup was a thing. Memories of my twenties are lost.

Yet we’re now entering a new era – thanks to the cloud, it’s seemingly impossible to truly delete anything from my iPhone now. Joanne Garde-Hansen, Director of the Centre for Cultural & Media Policy Studies at the University of Warwick, says that while we continue to curate photos for presentation and framing, we’re also taking lots more of photos of things we have no desire to keep: instructions, signs, screenshots. “In some ways, it’s no different from 30 years ago where you would go and collect your expensively produced photographs from the shop and only three of the 36 photos made any sense – the rest weren’t particularly good,” says Garde-Hansen. But the volume of pictures has exploded, and this creates a new problem: “There’s just an overwhelming amount of material, and a lot of it doesn’t get deleted.”

The task of sorting through everything has become momentous, meaning once a photo is taken you may never see it again, even if you do successfully keep it safe. Companies like Facebook and Apple have created “on this day” and “year in review” features where they periodically present users with old photos, an initiative that many people love. But this means that not only have we outsourced the storage of our memories to giant tech companies – now we’re also outsourcing the curation of our memories.

“The algorithms are starting to try and create narratives of your life for you, and you either accept them or you challenge them and create your own,” says Garde-Hansen. “It’s sometimes more chaos than conspiracy around who has access to [our data], and who’s got power over it. But people don’t seem to realise that they’ve been left at the mercy of large organisations.”

Nostalgia is a powerful emotion. As I was researching this story, Instax, the instant camera from Fujifilm, ran an ad campaign on the London Underground that stressed the value of a printed photograph over a hundred that only exist as pixels. As someone with an old photo strip from Berlin tacked on the wall next to my bed, I get that. A OnePoll survey of 2,000 people conducted on behalf of Instax found that a third of respondents would like to do a digital detox this year, and almost half long to participate in more “offline” activities. But as I was talking to my partner about this, he reminded me that blaming technology is lazy. He should know – my partner (and the other person in the photo strip) Luke Abrams, was a product manager on the team that created Microsoft’s first consumer cloud storage product in 2007.

“We found it really striking that after hurricane Katrina in 2005, people were looking through the wreckage of their houses and grabbing hard drives,” says Luke. Although early photo storage was a mess – your noughties memories are undoubtedly scattered between old hard drives, USB sticks, laptops that haven’t been fired up in years, and dusty CDs – Luke says that even during the wilderness years, digital may well beat analogue storage when it comes to longevity.

“Those hard drives are good for a lot longer than a box full of negatives,” he says. A hard drive that’s been through a hurricane will probably have some data loss, but assuming you take reasonable care of them, CDs and other optical media should safely last centuries.

“Magnetic media, so things like floppy disks, will keep most of its data for 30-40 years unless they’re exposed to a strong magnet,” Luke says. Hard drive lifespans depend on how heavily they’d been used – spinning media drives are more vulnerable than flash drives, but both should fire up again decades later assuming they weren’t too worn out when put away. But an old laptop would probably be infected by viruses within minutes or even seconds if connected to the internet, warns Luke: “With anything more than ten years old, you’ll probably need an expert to help you retrieve media.”

When the technical challenges of saving data are solved, the problems that remain will be human

The road from analogue to digital hasn’t always been user-friendly, as the early days had competing formats, crashing hard drives, slow internet connections, and less than intuitive interfaces. The principle of data portability (enabling data to be transferred between platforms) was mandated for all companies operating in Europe in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018, and Flickr now allows users to download their archives. Yet when Mike Johnson, a 36-year-old Flickr user from Missouri, USA, was prompted to download his Flickr archive by the end of the free era, he found it was a mess.

“I put a lot of effort into organising my photos on Flickr,” he tells me over Skype. “I have over 10,000 photos and they came out in 13 zip files, but they’re not organised in any [logical] way such as by year or by collection.” The metadata file was similarly confusing, and when he downloaded his Facebook data it was no better. “When you choose to leave a platform where you’ve uploaded a bunch of data, I wish the data you receive as an export would be more usable,” says Johnson. “My basic understanding is that right now, I’d need to become a software developer to access data in a way that is actually useful to me.”

Even when the technical challenges of saving data are resolved, the problems that remain will be human. What happens when you forget the answer to your password-retrieval question, or you have a bad divorce and lose access to your shared digital storage, or someone dies and loved ones can’t access their files?

“Authentication is the last great hurdle – ensuring that the people who should have access to data have access even if they lose their passwords, and ensuring it’s sufficiently protected against intrusion,” says Luke. He looks at me pointedly – have I made sure I have multiple ways of recovering all my passwords? Although I have downloaded my Flickr archive, I suddenly feel a little faint. Luke nods: “We are still in a place where you can lose everything.”

So what am I doing with my photo archive? I’ll copy the newly downloaded photos from Flickr onto a second cloud service, but I’ll also print my favourite digital photos and make albums. Maybe I should scan all my old prints so they’re backed up too? I’ll keep sharing photos on Instagram, but as I figured during a recent trip to Japan, social media etiquette means you can’t really post more than one or two photos per day. As I chose my Japan photo of the day, I realised that the sharing aspect of photography has become separate from storage – I also want a place to put everything that isn’t curated, and I’m willing to pay for security.

I’m past the point where I’m simply not thinking about how I’m storing my memories, and that’s probably the most important step of of all. I may never be able to fully bridge the five-year gap between my old analogue photo archive and my newly secured digital one – I still need to dig through my drawers and examine some old thumb drives. Maybe I’ll get lucky and find some lost years hidden away in there. But at least I know that from now on, everything will be backed up – in more than one place.