Dries De Roeck

Draw the internet: the web as seen by the world’s school children

understanding how the world’s school children perceive the Web

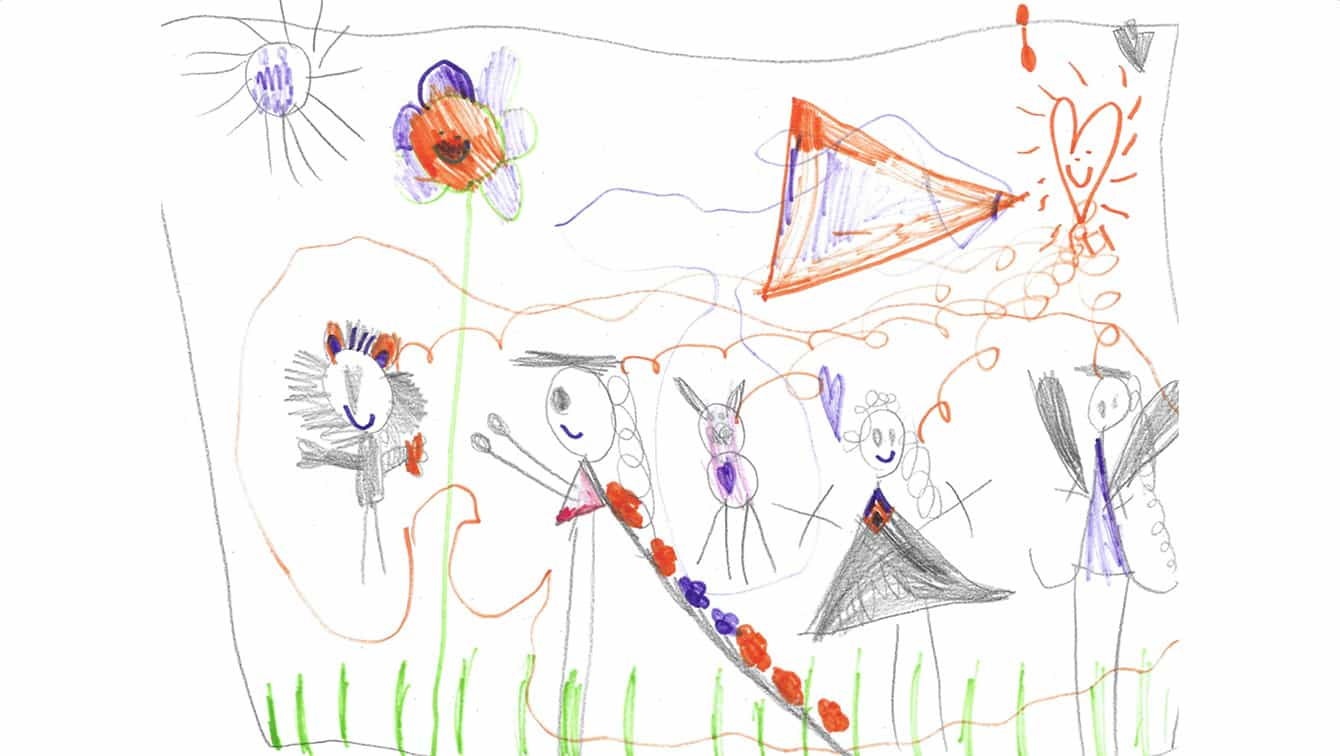

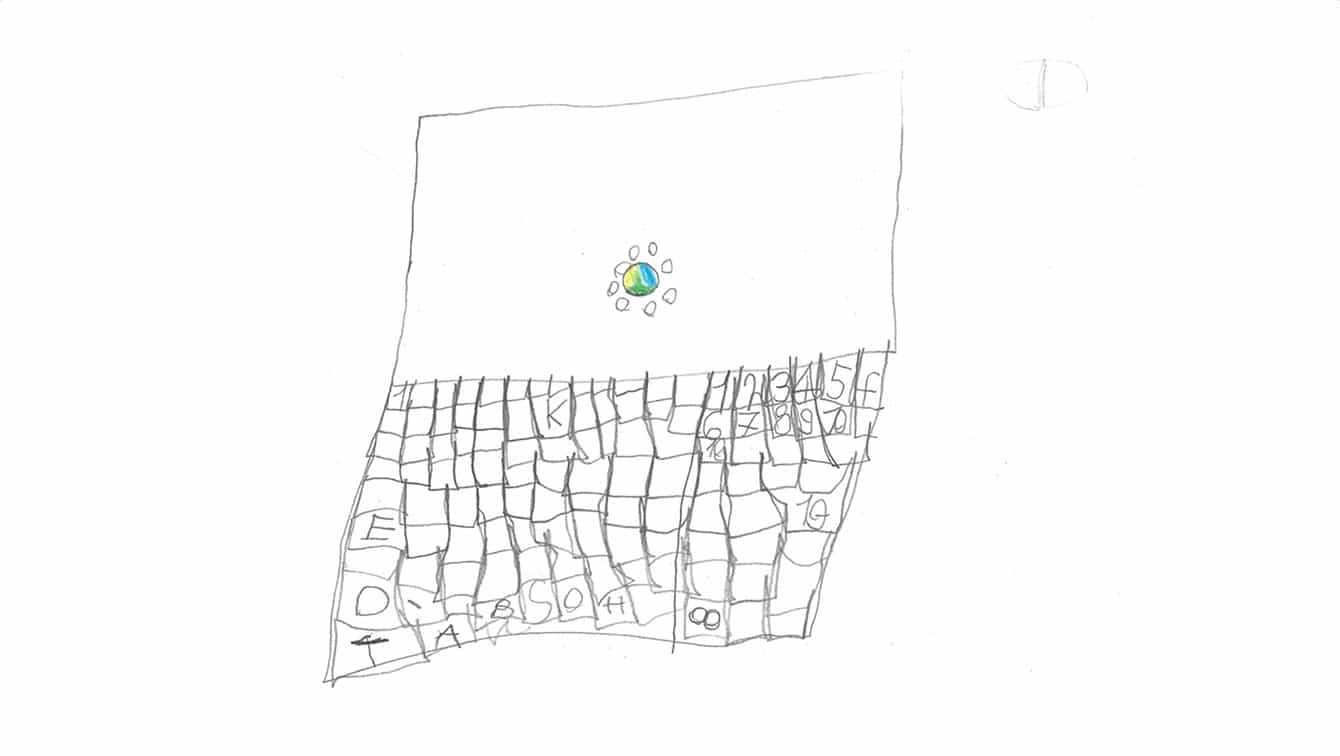

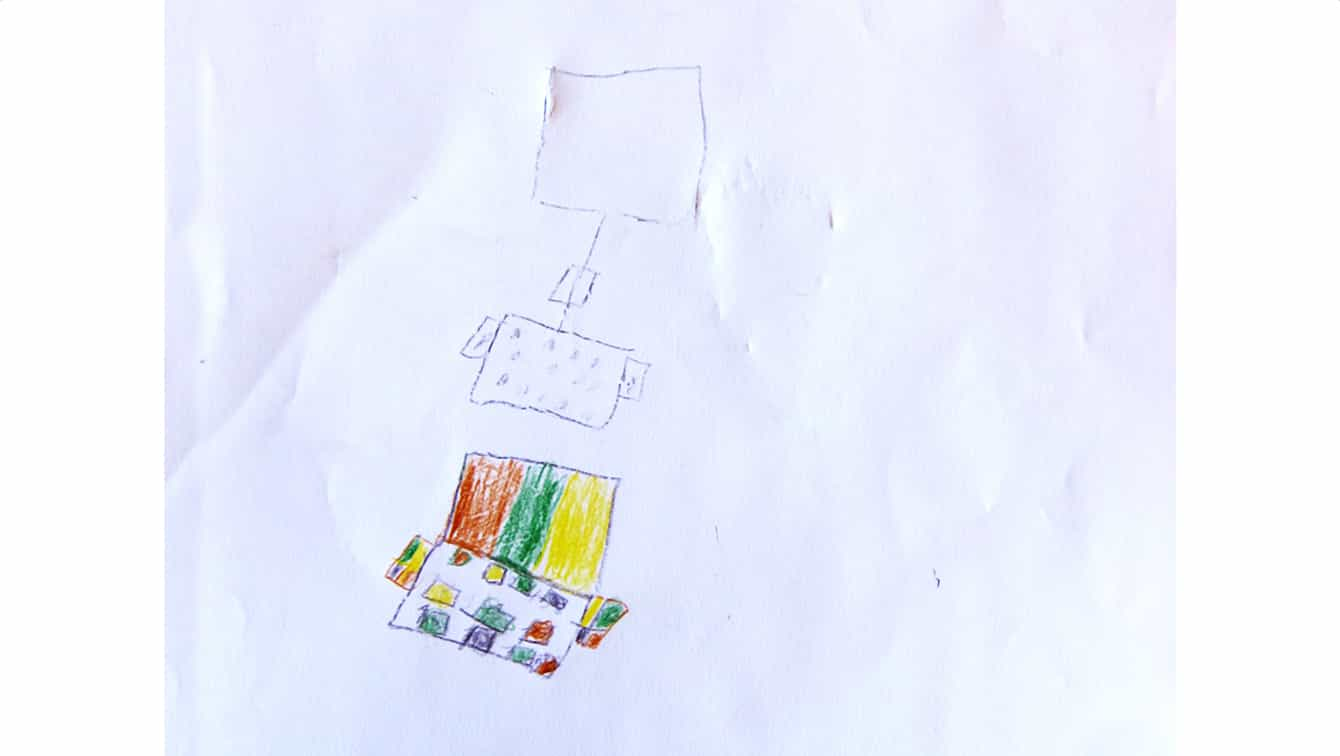

In order to think properly about the future of the internet, we need to look to younger generations. As part of our quest to understand what the internet is – and could be – we gave primary school children one seemingly simple instruction: “Draw the internet”. No rules, no judging – anything goes.

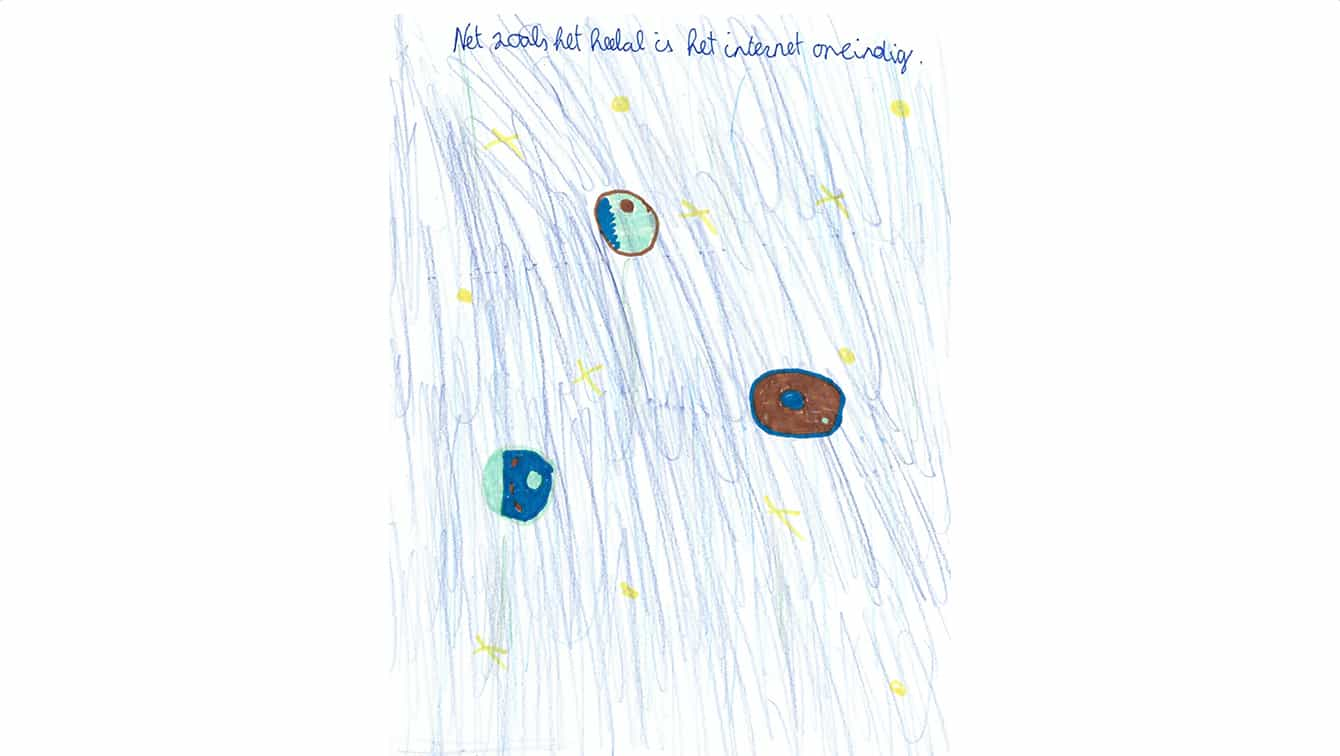

For young children, the internet seems to be something that floats in the air and connects things

The aims of our project were twofold. Firstly, by approaching different age groups (ranging from six to twelve years old), we hoped to see how perception of “the internet” evolves over time as a person grows. Secondly, by engaging with two different cultures, we hoped to illuminate the cultural differences in how we experience the internet. One set of drawings was collected in a local European school in Belgium, and another set in a local African school in Senegal.

In total, about 300 drawings were collected from both schools. Out of these 300, a selection was made that highlights how both age and culture influence our perspectives on the internet. Explore this selection using the slideshow at the top of this page.

The abstract drawings are inspirational – they make you think about the internet in unexpected ways

The work was enlightening in many ways, but we had a few core insights. In short, we found:

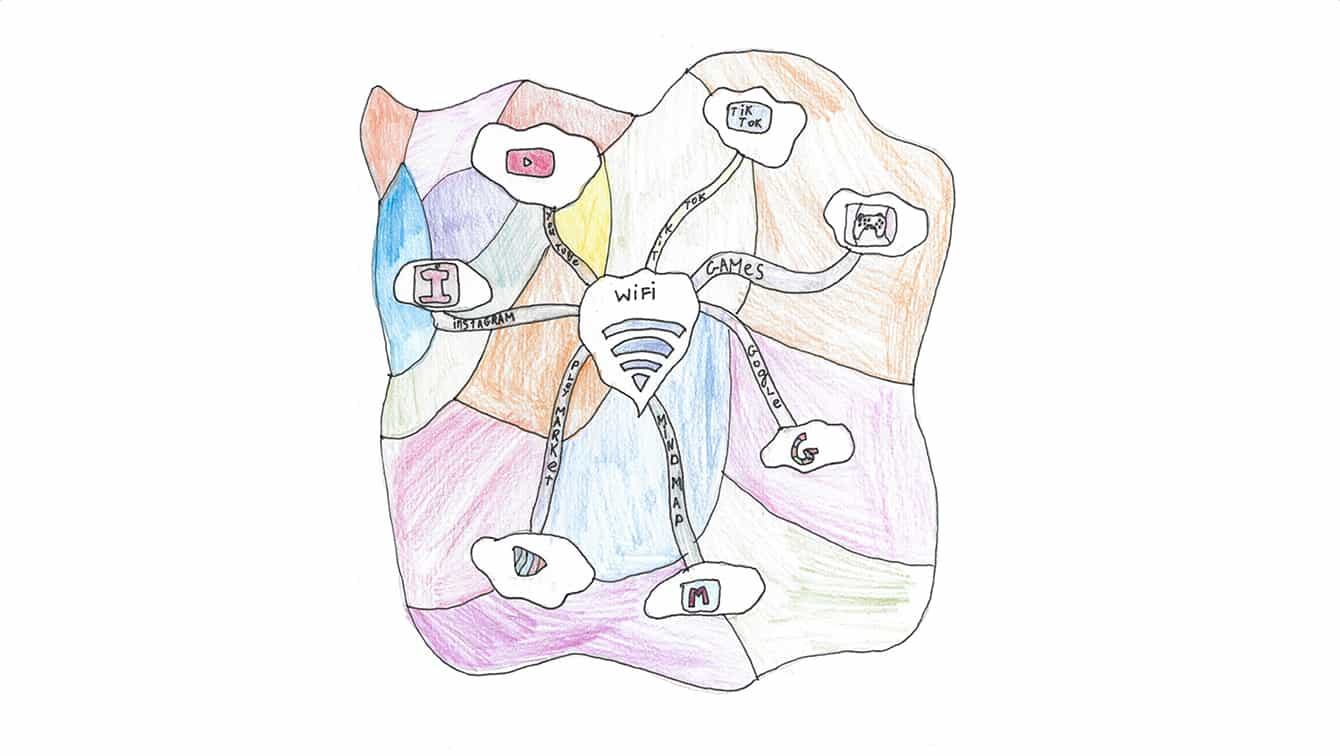

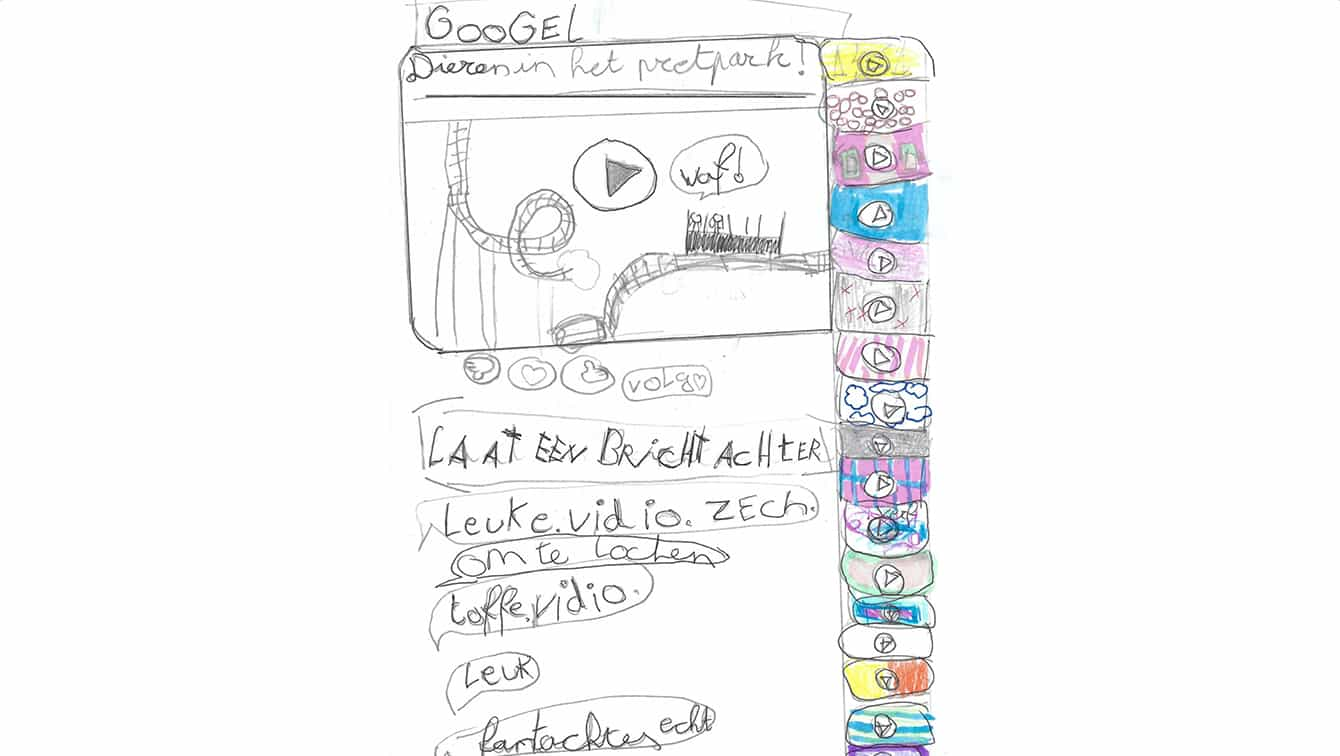

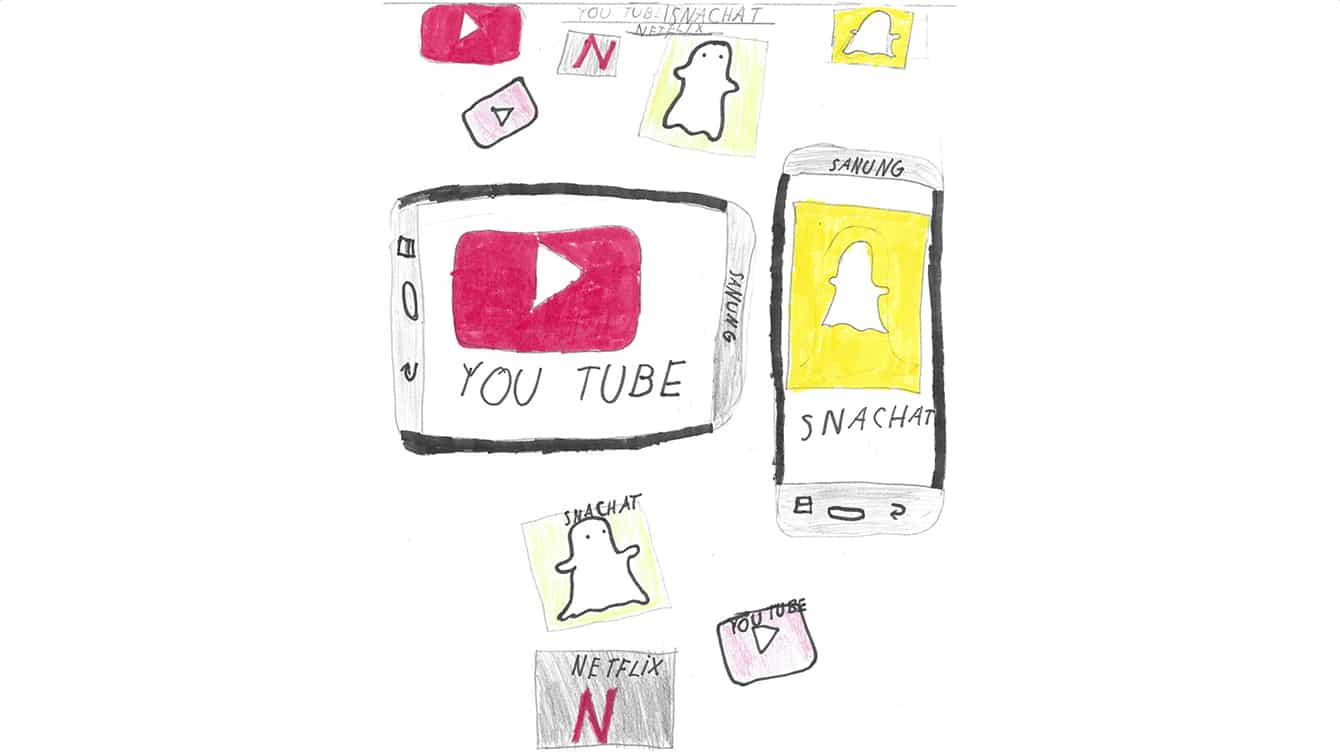

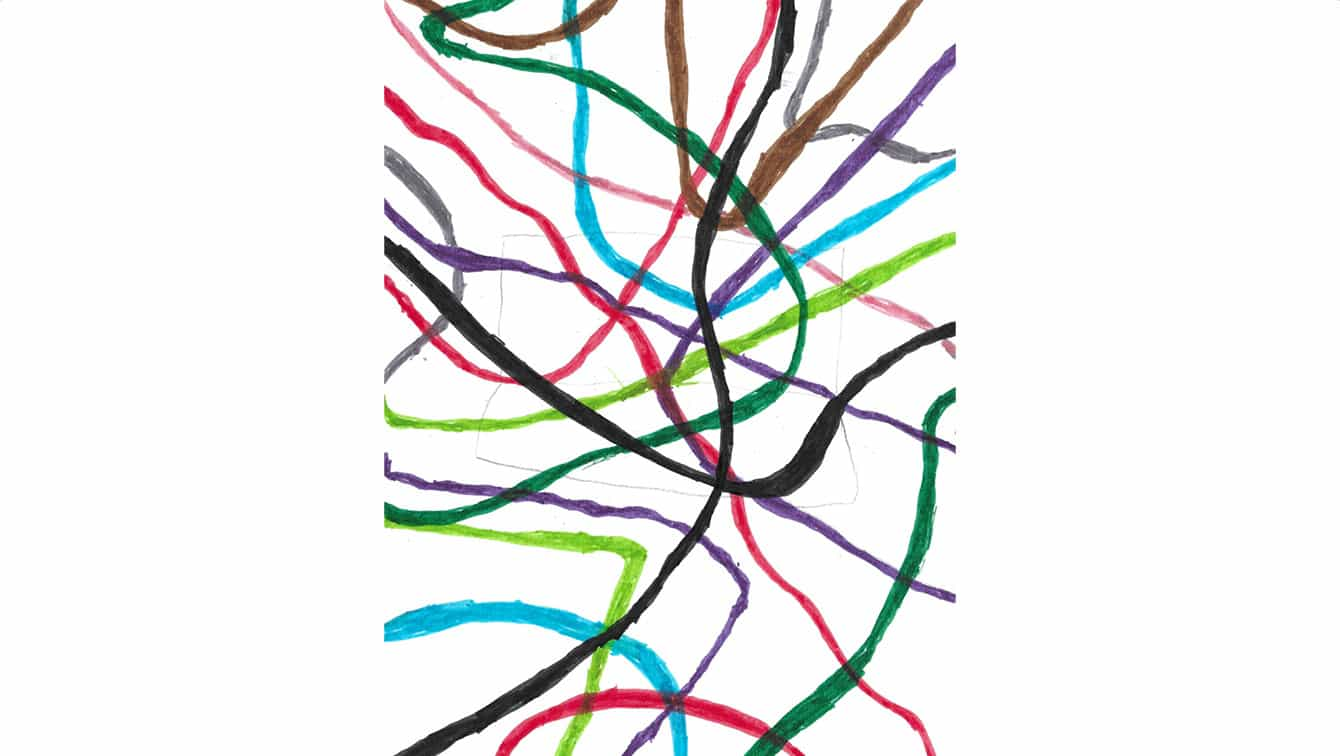

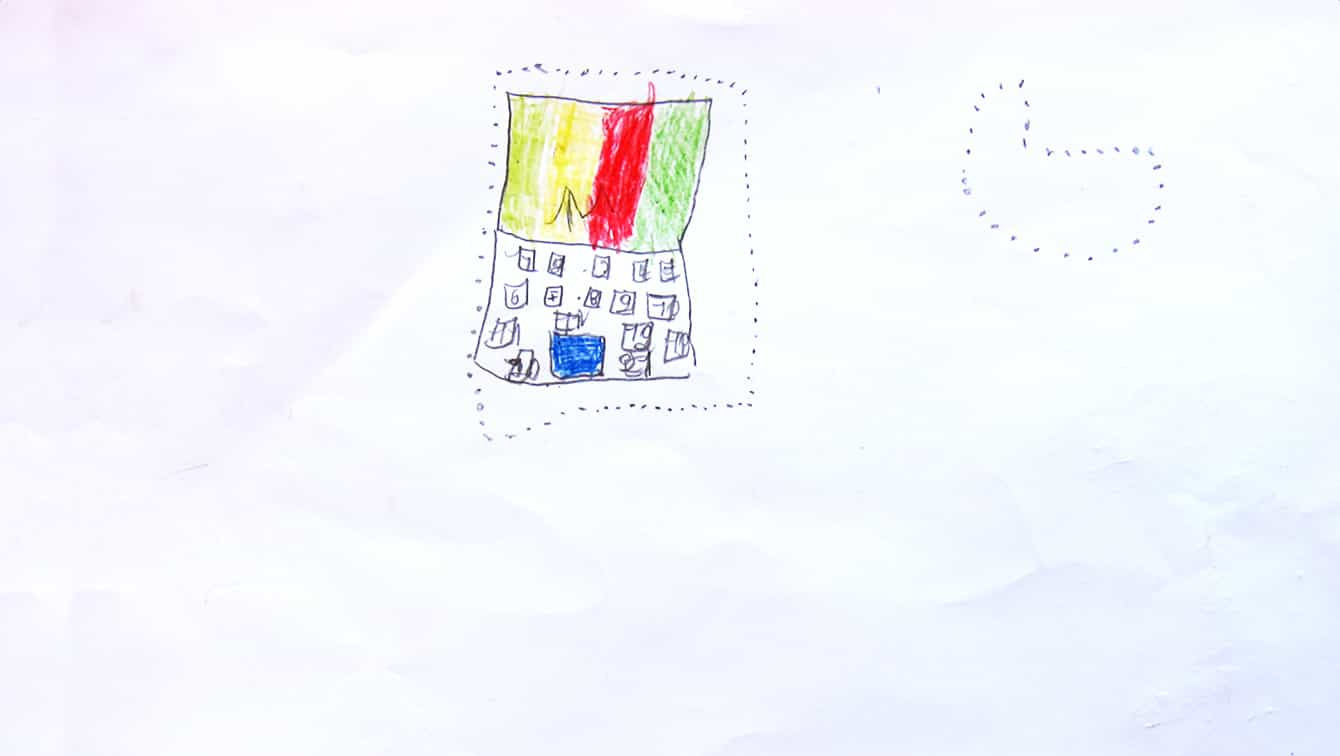

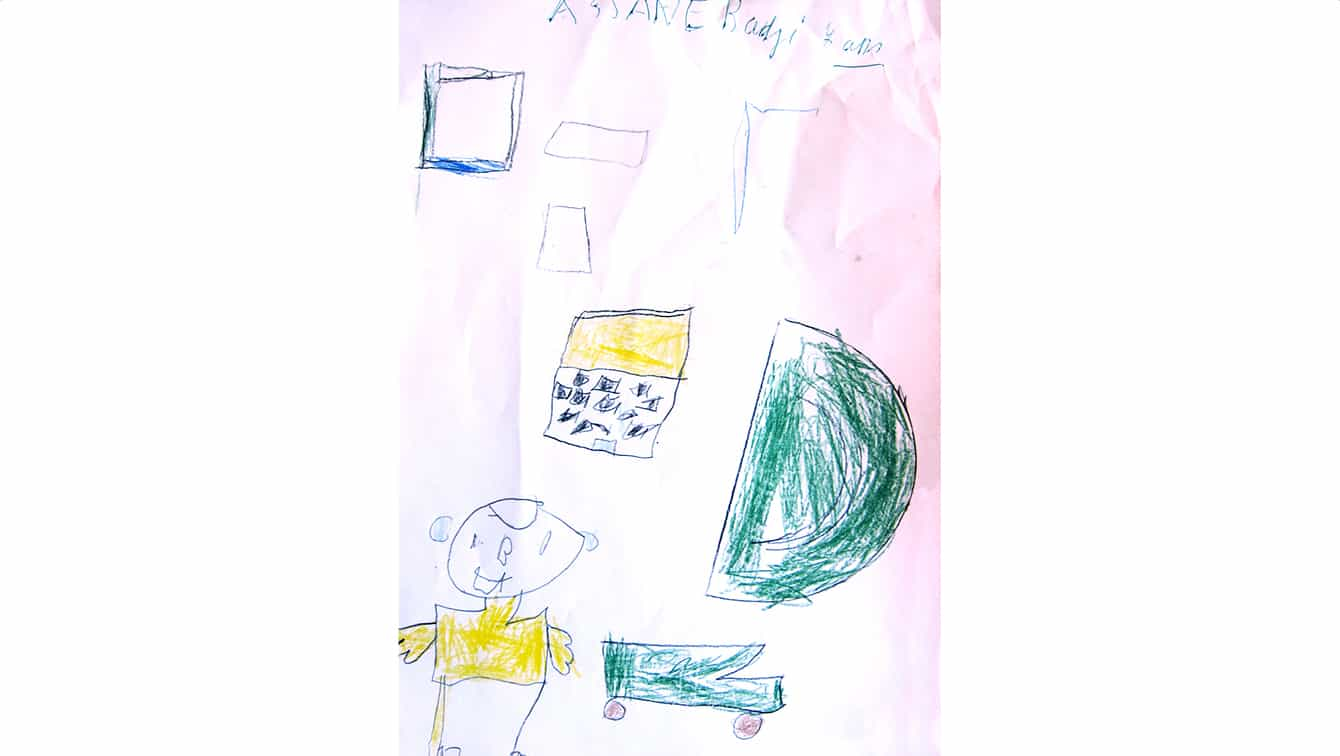

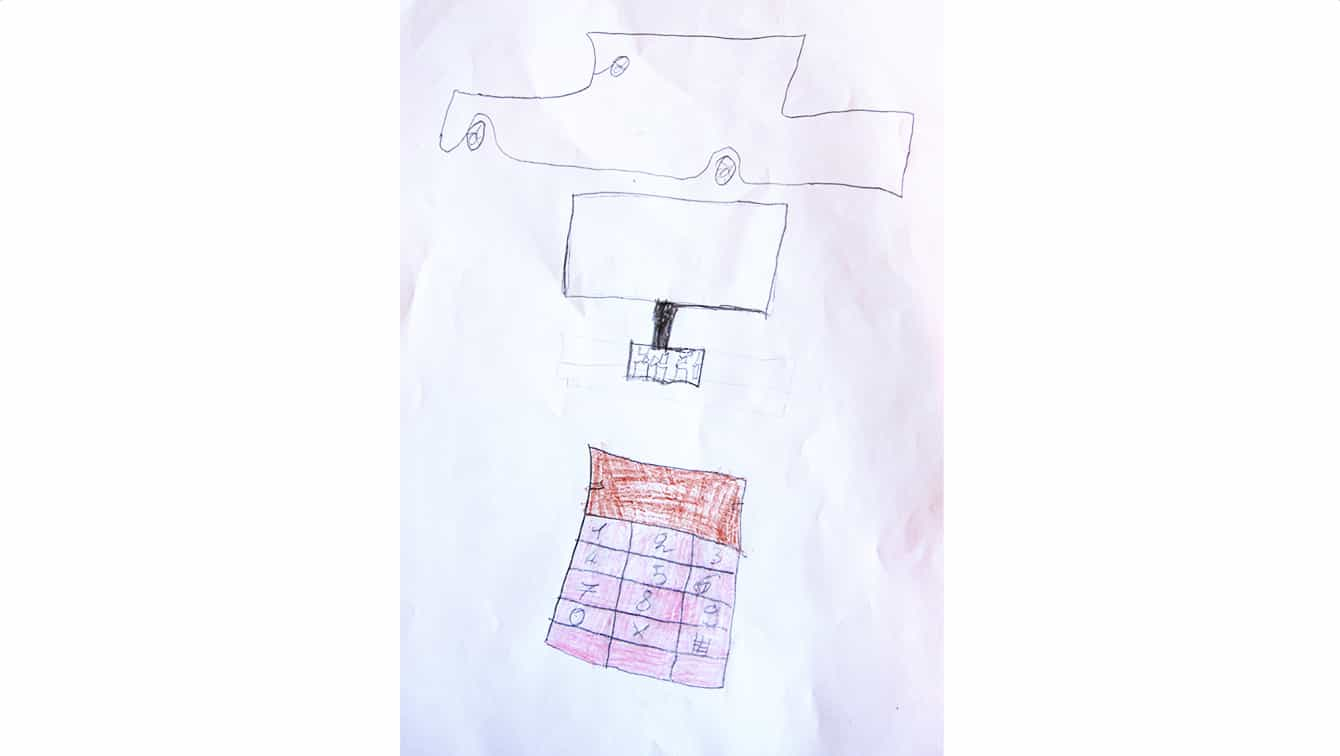

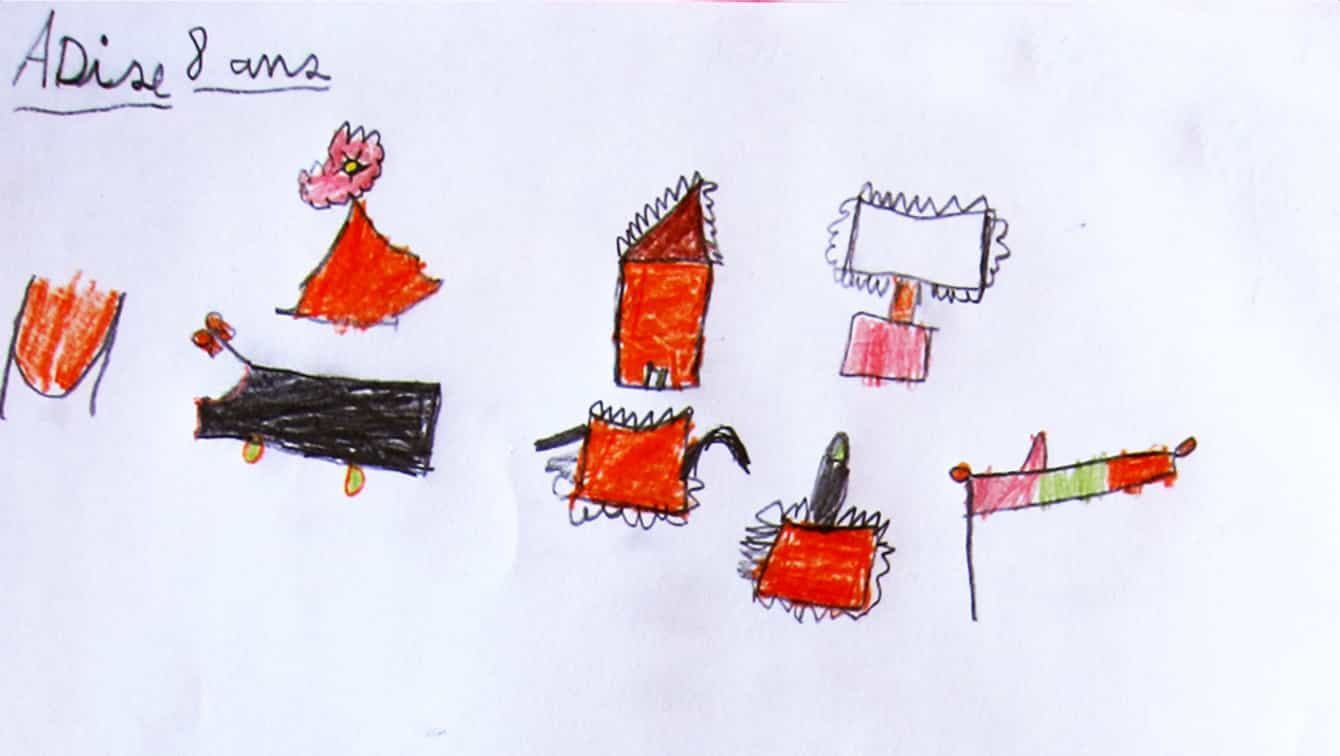

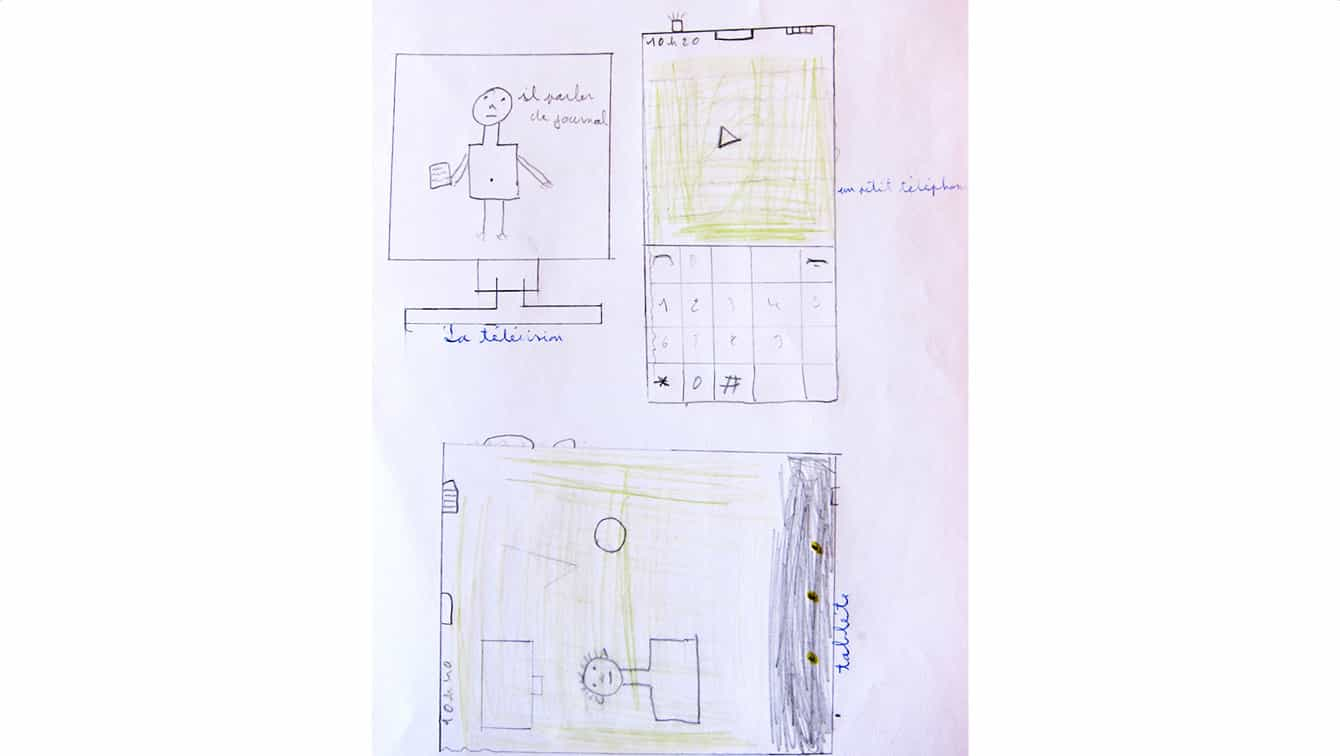

- Younger children (aged six to eight) tend to draw “networks” of people, houses, clouds, and flowers. For these children, “the internet” seems to be something that floats in the air and connects things. As they get older, their relationship with apps and brands quickly becomes dominant. “The internet” gets diminished to icons that live on smartphones, tablets and computers.

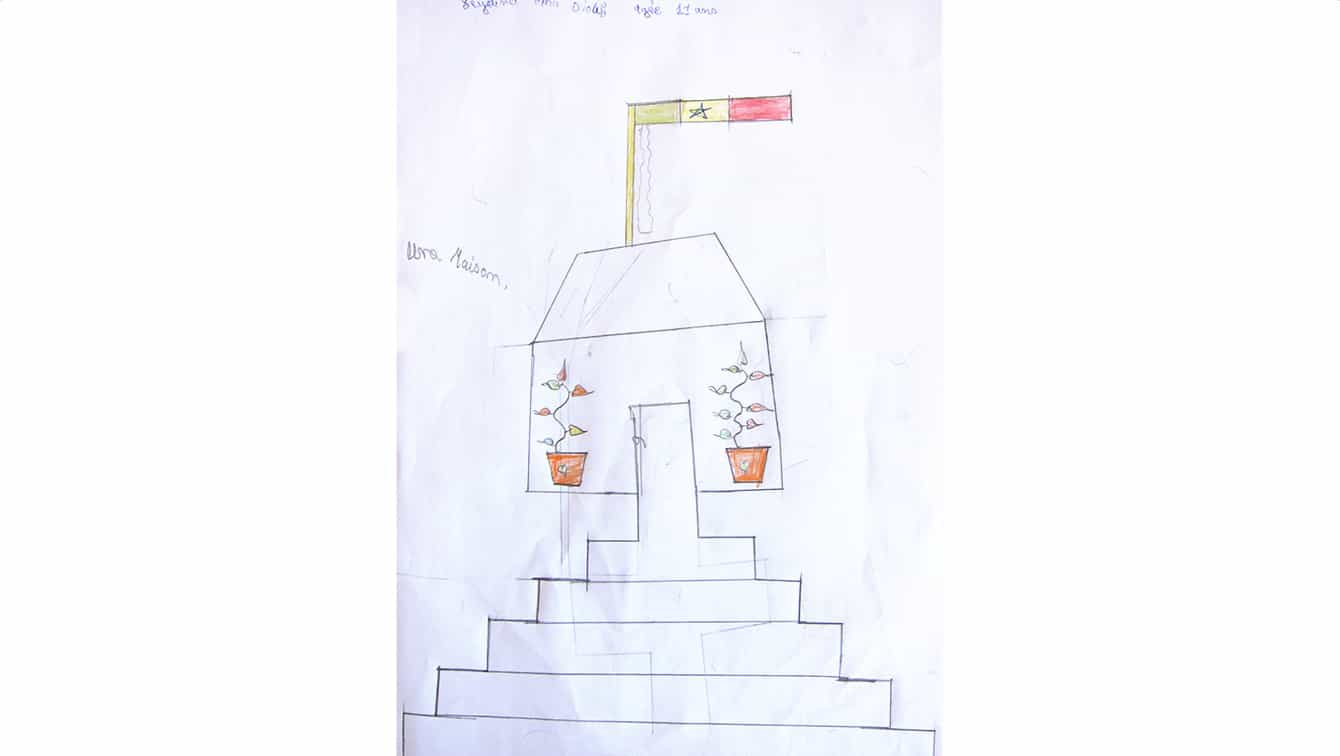

- In Senegal, children struggled to imagine something that would represent the internet. One reason for this is that the word “internet” is hardly ever used by local people, and instead people tend to talk about “connecting” or “making connection”. Because most internet consumption happens through smartphones in Senegal, little distinction seems to be made between transferring data, sending a text, or voice calling someone.

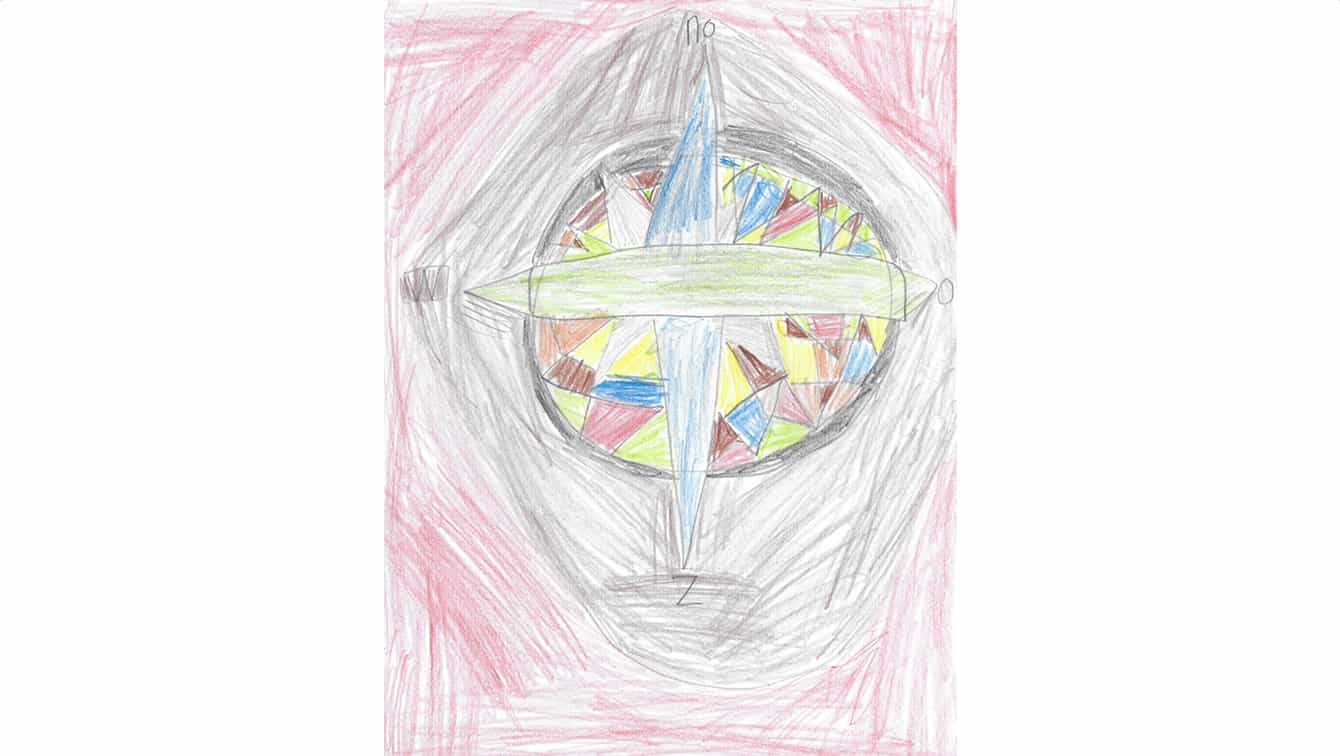

- The exercise was deliberately very abstract. Some children quickly found strategies to re-interpret the question in their own way, while others found this more difficult. For example, some children drew lines linking abstract objects together, representing a “network”, while others struggled to get started and ended up copying existing drawings from their jotters.

- It was inevitable that children would copy and rework each other’s work. This was clear in both school groups – if someone started to draw a phone, then a couple more phones would quickly appear on the sheets of paper around that child. In retrospect, the project could be repeated as a group exercise instead of an individual one.

- Some drawings are a clear reference to the assignment given while other children clearly did not totally understand what the idea was all about. In the end, the latter are often very inspirational to look at – they make you think about “the internet” in unexpected ways. For example, a drawing of a car inspires us to visualise the movement of data; drawings of houses make us think about how communities exist online; and a child’s picture of a flag hints at how identity works on the internet.

- We had no expectations and deliberately didn’t want to define what would be a “good” or “bad” interpretation of the question. Our results can be explored with a very open mind in order to provoke further thought and conversations.

With thanks to both primary schools, BS De Wilg (Lint, Belgium) and Les Cajoutiers De Warang (Warang, Senegal), without whom this project would not have been possible. In particular, thanks to Katleen Vleugels (BS De Wilg), René Devinne, and Sophie Camara (Les Cajoutiers De Warang) for supporting this project.