Russel Hlongwane

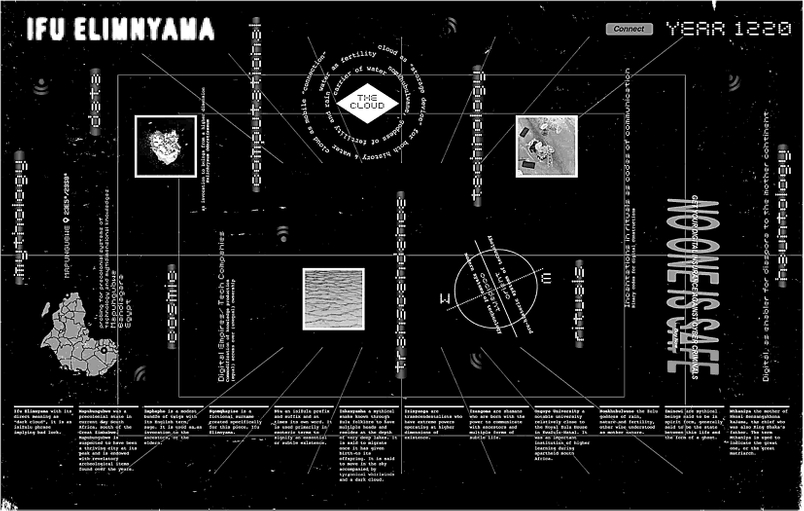

Ifu Elimnyama, The Dark Cloud: a short film

Ifu Elimnyama is a six-minute experimental video exploring the dual meaning of the cloud, the dark cloud. With the pervasive nature of cloud culture comes a potential clouded culture, a troubled culture. In isiZulu, we would say: “Wehlelwe ifu elimnyama” – you have been beset by a dark cloud!

Introducing the concept

Set in the year 1220 in the precolonial Great Ruins of Mapungubwe, Ifu Elimnyama: The Dark Cloud places Zulu cosmology, mysticism and sacred rituals within a digital framework as a reflection on – and critique of – the internet and its future.

The provocation

The internet, with all its good intentions, is a place of promise and (latent) destruction. Humanity, for better or for worse, has been understood through algorithms, networks, and interfaces. But, could we propose an understanding of the digital beyond algorithms and binary systems? Can we converge the algorithmic and the scared, the scientific and the mythical, as a means to propose an inclusive lexicon of the internet, and its future?

The internet as a system and form of technology is attributed to the West, however, here we see that the so-called global south are active agents of technology in much more transcendental ways. The work therefore invites the viewer to think about mythology, cosmology, technology and transcendence all within the same frame.

Background to the characters, site, epochs, and rituals

uMalanje, the protagonist, is an interstellar flaneur who broke away from a small group of an advanced black civilisation. This civilisation migrated to the fourth dimension after much of the black race was decimated in the once-thriving metropolis-kingdom of Mapungubwe (S 22’ 14’ 37’, E 29’ 24’ 02’) on planet earth. Over millennia, the civilisation evolved into imingcwi – figures that are known through Zulu folklore and mythology. They travel by riding the light spectrum through a black hole to return to the site of Mapungubwe to deliver a forewarning to the village of Nqomqhayise.

Glossary

Ifu Elimnyama: an isiZulu phrase implying bad luck; its direct meaning is “dark cloud”

Mapungubwe: a precolonial state in current day South Africa, south of the Great Zimbabwe. Mapubungubwe is suspected to have been a sophisticated thriving city at its peak, it is estimated to have existed between the years 1220 and 1290

The year 1220: the year that the state is suspected to have dissipated

Imphepho: a modest bundle of twigs used as an invocation to the ancestors, or the elders

Nqomqhayise: a fictional surname created specifically for this piece

Ntu: an isiZulu prefix and suffix and at times its own word. It is used primarily in esoteric terms to signify an essential or subtle existence or form of life

Inkanyamba: a mythical snake known through Zulu folklore to have multiple heads and reside at the depth of very deep lakes. It is said to migrate once it has given birth to its offspring. It is said to move in the sky accompanied by tyrannical whirlwinds and a dark cloud, therefore it has never been seen. Inkanyamba is known by other names around the SADC region

Nomkhubulwane: the Zulu goddess of rain, nature and fertility, otherwise understood as mother nature

Imingcwi: mythical beings said to be in spirit form, generally said to be the state between this life and the form of a ghost

Nkosazana: an isiZulu word for mermaid

The plot

Nqomqhayise is the shrewd business-minded member of the Nqomqhayise royal family that was given custodianship of black history since time immemorial. Nqomqhayise is now secretly flying to Silicon Valley to entice venture capitalists to invest in his elaborate digital empire. He has corrupted the cloud in which black history and ontology is stored, and wants to migrate this data to one of a kind servers that his start-up will manufacture. The people of Mapungubwe will therefore have to “pay for access’’ to their own history and knowledge of their forebears.

Around the same time period, the mythical snake Inkanyamba began its migration across the sky. Soon after it took flight, its GPS lost connection to the internet, and Inkanyamba remained locked in liminality for aeons with its accompanying dark cloud. During this time, there is no rain, no knowledge production, and consequently no growth over the region of Mapungubwe due to a lost “connection”.

It is this threat to the future of the black civilisation that has prompted imingcwi to traverse across space-time to deliver a forewarning to the people of Mapungubwe. Imingcwi have commanded a team of geeks to journey to Nairobi to learn the most advanced systems of digital networks in order topple Nqomqhayise’s devious scheme. uMalanje has therefore returned to witness this pivotal moment.

To accept the broken promise of the internet is to accept the insidiousness of capitalism

Questions

- Who (or what) do we entrust with codes to our digital existence?

- What do we expect from those whom we entrust with this power?

- What is implied and what is at stake when the trust is broken?

To accept the broken promise of the internet is to accept the insidiousness of capitalism. Institutions of higher learning commodify knowledge systems, essentially monetising epistemology. The internet presents “free information’’, but this comes with the commodification of clicks; user history and surfing habits go to the highest bidder.

How is the internet different from the Neo-capitalist existence under which we are (under)valued? More pertinently, given the scrutiny and subtle forms of surveillance under which the black body currently exists, how can we neutralise the internet’s engineering of blinded algorithmic processes that weigh in on black folk in the justice system? Is race – whether, deliberately or indeliberately – being engineered into the internet?

Meanings

To burn imphepho in local custom is an invocation to your ancestors – a connection to knowledge located in the ether. However, in the story, we see the parallels of “connection” as both transcendent and technological. Again, in a number of African cultures, a pregnant cloud resembles rain or fertility – more specifically rain is inextricably connected to uNomkhubulwane, the goddess of fertility who sits beside the creator. This triangulation of the cloud as connection, as fertility, and as mythology, allows us to imagine new realms of the internet.

We can understand the popular phrase “to go online’’ as an instant migration to another dimension just like imingcwi migrating from the fourth dimension to the third through a black-hole, as we see in the narrative. Through their journey, imingcwi have to contend with exposure to extreme radiation and swirling comets through warped time. Likewise, the instant migration to the digital is also increasingly reshaping the physiology of our brains and neurotransmissions.

Instant connections have changed our behaviour, which is evident in the way the diaspora connects to Africa. Thus, activism has spread wider and created a kind of numbness and slacktivism. To click “support’’ on your MacBook is a world away from showing up at a Black Lives Matter protest and risking your black body. To this end, the story also hints at the “hauntology’’ of the enslaved that were forcefully removed from their soil, who await the cloud in order to “connect’’ to their cousins back home.

The internet does not operate on direct action, but implied actions and intentions

The video weaves in a series of implied sacred rituals for several reasons, chiefly because the internet does not operate on direct action, but implied actions and intentions. The implied rituals are ways in which we (as Africans) can code our roots into the digital, consequently archiving that which has guided us for millennia. Through this archiving comes agency and ownership of the digital.

Nairobi remains the most digitally-connected city on the continent, hence why the task team in this narrative is sent to learn systems of planting fibre networks so that they can return to Mapungubwe and connect the continent, therefore achieving the long held dream of a connected Africa, The Pan Africa.

However, one question remains: does a digital space have the capacity to carry ontologies, not just data?